I wrote this article in April 2015, and was updated in March 2025. The brand in the lower right corner of the title picture was mine from when I had my Corriente cattle ranch.

Montana is a marvelous juxtaposition of old and new, archaic and modern, and if you need an example of that, ask some random Montanans what branding is.

Get a rancher, historian, or just plain romantic and you’ll hear a tale of cattle branding. They’ll speak of the sound of bawling calves, the smell of seared hair and flesh, and the legends of the cattle rustlers.

Corner someone in a suit walking out of an advertising agency and they’ll regale you with stories of successful (and not so successful) attempts to control the image of a business or organization. They’ll talk about brand management, logo designs, PR, and social media. See my branding of the Yellowstone Wildlife Sanctuary as an example.

Surprisingly enough, they’re really talking about the same thing.

Although modern business or community branding can be ephemeral, it typically centers around a logo: a symbol used to represent the organization or product line. That is precisely what a cattle brand is. There’s a reason that a cowboy loyal to his outfit was said to be “riding for the brand.” If the Bar RS ranch was known for quality beef, buyers would look for that brand on the animals.

Montana has been registering brands since 1873, providing ranchers with a way to uniquely identify their cattle and horses. This was especially important in the days of free-range cattle. If my herd got mixed in with your herd, their brands would be the only way to identify whose were whose.

© Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives

Early ranchers picked simple and memorable brands, often a single letter or symbol. Brands like that aren’t available any longer, and if you own one, make sure you reregister it when it comes due. Those old one-letter brands are worth some money!

But there’s a dark side to the easy brands, too, and that takes us into the world of cattle rustling.

If your brand was Bar-A (a capital A with a line over it), and your registered location was the cow’s left hip, then any cattle in your county with a Bar-A on their left hip were yours. Easy, right? But what if I registered Bar-AB in the next county over. My brand looks just like yours, except with a longer bar and an added letter. I could steal a bunch of your cattle and change the brands, and all of a sudden they’re mine!

The brand registry and the local brand inspectors became good at preventing this kind of hijinks. They might require that if my brand is too similar to yours, I have to move it to the other side, or put in on a shoulder instead of a hip. They might simply refuse to issue a registration if my ranch is too close to yours. On the other hand, it could make sense to just register a brand that’s harder to modify.

But that’s a thing of the past, right? Have there really been rustlers since the Johnson County War of the late 1800s, with its lynchings and assassinations? Yes, there have.

In 2009, Richard D. Holen of Wolf Point, Montana was found guilty of rustling 39 head of cattle. Brands from eight other ranches and evidence that Holen had been modifying brands contributed to his conviction. But that’s just a drop in the bucket.

A 2009 story from The New York Times carried the headline, “Cattle Rustling Plagues Ranchers.” A 2011 Reuters article says that “In Montana alone, investigators have recovered more than 7,300 stolen or missing cattle worth nearly $8 million during the past three years, numbers believed to account for just a fraction of the problem.” And a 2013 NPR story stated that, “In Texas and Oklahoma, over 10,000 cows and horses – mostly cows – were reported missing” in 2012.

In May of 2021, Joshua James Chappa from Bozeman was sentenced to 2-1/2 years in prison and ordered to pay over $450,000 in restitution for cattle theft.

With roughly 2.5 million head of cattle in Montana alone, rustling still exists, and it’s right here in our own back yard.

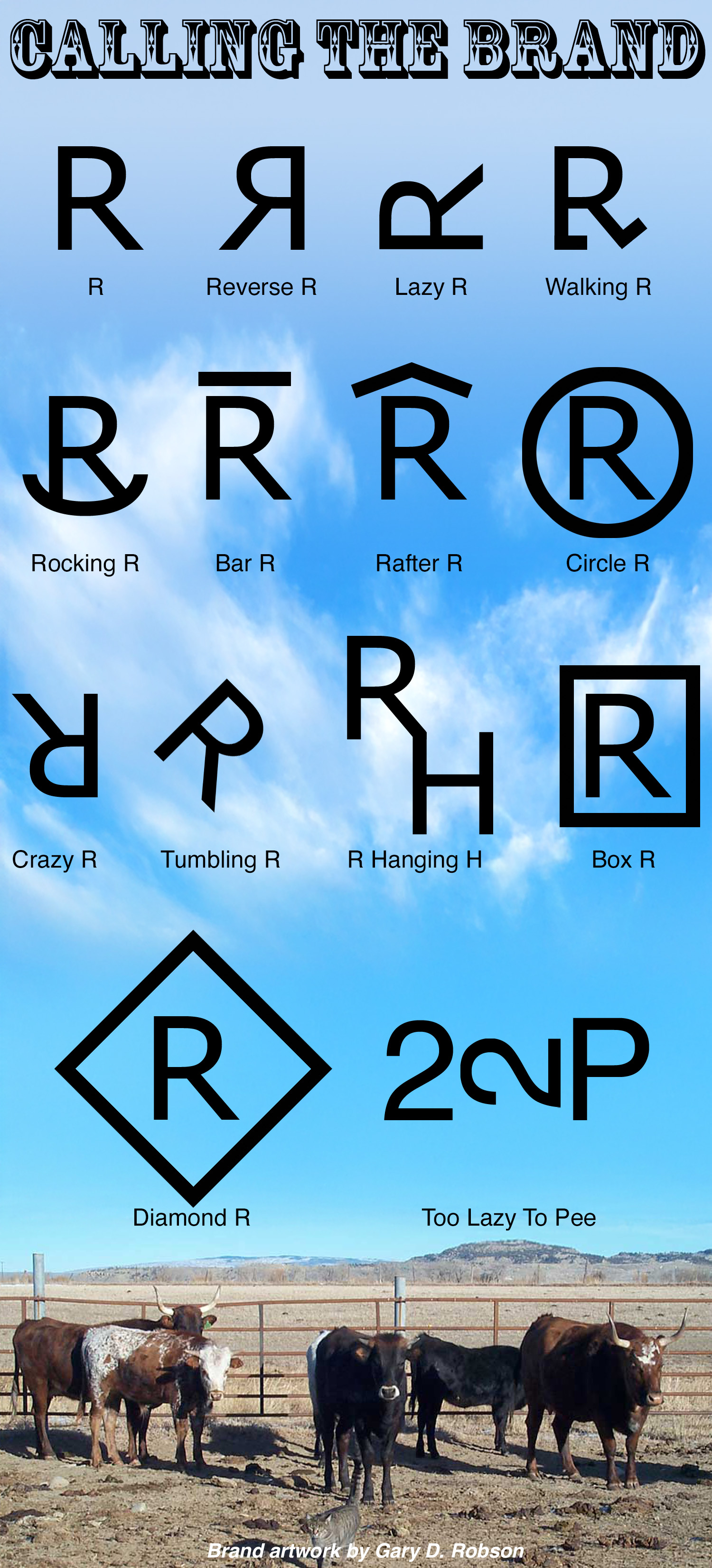

Nonetheless, branding carries a rich history and a language all of its own. Trying to describe a brand could be complicated, so ranchers developed a specialized way of reading the symbols, called “calling the brand.”

The three rules of reading brands are that you always read left to right, top to bottom, and outside to inside. That’s why an H with a circle around it is called “Circle H,” not “H Circle.” This system makes it easy to describe a brand over the phone or in a text message (or telegram) without having to transmit pictures of it.

Brand names have often been puns. The last one in the image above is a famous example. It would be read out loud as “2, lazy 2, P” which sounds like “too lazy to pee.” Brands also aren’t limited to just letters, like these examples. Brands can include numbers (calibers of guns make popular brands) and symbols like stars.

Brand design is an art with serious practical considerations, too. Brands are administered to cattle and horses by heating up branding irons until they are red hot and pressing them against the skin to leave a permanent mark. The hair won’t grow back on the scar, and it will stay there for the life of the animal. If a brand has small enclosed spaces (like the two circles in an 8), heat tends to accumulate there and the brand blurs, making it hard to read. “Open” letters like C, F, and V tend to work better than “closed” letters like O, R, and A.

Branding with fire has been around for centuries because it works, and it’s very easy to do in the middle of a field somewhere. There is a more modern alternative – although it’s more common with horses than cattle – that’s called freeze branding. As the name implies, the branding irons are super-chilled with dry ice and pressed against the skin. The freezing damages the color cells and the hair in that spot grows back white. Freeze branding is slower, as the hair needs to be shaved first, and can’t be used on white animals. Also, coolants like dry ice and liquid nitrogen are more expensive than a branding fire. So next time you look at a corporate brand on a billboard, think about how brands really tie us to a still-living part of the old west.